Hear the Conversation | Get the Book

The late bloom is often the most beautiful. Imagine a flower that opens, not with urgency but with quiet certainty, its petals unfolding slowly, deeply, until they rest in the full light of their truth. In the case of Jenny Dandy, author, grandmother-to-be, former executive, it arrives as a crime novel set-in classic New York architecture.

The late bloom is often the most beautiful. Imagine a flower that opens, not with urgency but with quiet certainty, its petals unfolding slowly, deeply, until they rest in the full light of their truth. In the case of Jenny Dandy, author, grandmother-to-be, former executive, it arrives as a crime novel set-in classic New York architecture.

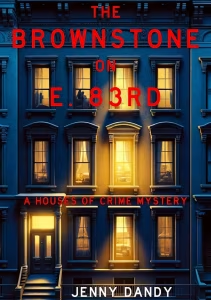

The Brownstone on East 83rd is not just a literary debut; it is the exhalation of a long-held breath. Jenny is sixty-five, with a voice that carries the quiet authority of someone who has, finally, fulfilled a dream. “I always considered myself a writer,” she tells me. “But lots of other things got in the way.”

Those “other things” she mentions with wry understatement, three children, a husband’s unique start-up, are not interruptions so much as the lived experience from which her writing now draws its weight.

To call her a “debut author,” as we tend to do, feels disingenuous, as though the intervening years of observing, absorbing, and reflecting were a prelude rather than the story itself. Jenny Dandy’s entrance into the literary world is not a youthful declaration but a quiet arrival, the long-anticipated turning of a key.

What compelled her to begin? Not a muse or some long-dormant plot. Rather: a narcissist. “I started exploring a manipulative narcissist,” she says, her tone clinical, almost amused. “I wanted to understand how someone like that works, and why I didn’t spot them when they were in my orbit.”

From this psychological puzzle, the character of Isabelle Anderson emerged, glamorous and opaque. But Dandy quickly realized a narrative paradox: true narcissists are fundamentally hollow. “She was supposed to be my main character, which you can’t have. There’s no there there.”

And so, Isabelle’s story became the space around which the novel formed. The protagonists became Ronnie, a gender-fluid teenager with more emotional truth than polish. And Frank, the dogged FBI agent whose instincts make him a worthy counterweight to Isabelle’s charm.

We writers like to plug each other’s creative style into one of two worlds. We meticulously plot every twist and turn in our tales, or roll the dice and let the muse of the moment guide us… hopefully home. In Jenny’s case another analogy feels appropriate. “I don’t plot,” she insists. “I quilt.”

Quilting, as Jenny describes it, is less about strategy than intuition. Small scenes, vivid fragments, bits of dialogue, all stitched together in time. In one such patch, she sent Ronnie on a mundane errand, only to watch the character stop on a bench in Central Park and simply refuse to get up.

“I could not write her off the bench,” Jenny says. “I left my desk. I thought, ‘I’m not a writer. I’ve tricked myself.’”

The crisis resolved not with willpower but with surrender. In a moment of distraction, folding laundry, moving through her home in the dreamlike fugue familiar to anyone stuck in a conundrum, she realized: Ronnie knew she wasn’t the one to go on the errand. Another character was needed.

The story resumed.

There is something of the séance in her process. Her characters don’t perform; they inhabit her. They interrupt sleep, lodge in her chest, refuse to obey. “It sounds a little loopy,” she admits. “But they’re real to me.” In another life, this might have been madness. In this one, it is art.

What keeps her grounded is craft, learned, not inherited. Jenny Dandy is a proud alumna of the Lighthouse Writers Workshop, a crucible for Denver’s literary community It was there, during a two-year intensive project, that she learned how to shape her instincts into narrative muscle.

Her mentor, noir writer Ben Whitmer, drilled into her the discipline of scene: start late, leave early, kill your darlings. “I was trying to trim a bloated paragraph,” she remembers, “and he looked at it and said, ‘Cut the first three sentences. You’re just warming up.’” It was a revelation.

“I realized I was afraid the reader wouldn’t get it if I didn’t lead them in. But you don’t need to lead. Just let them catch up.”

And they do. Readers, she’s found, are smarter than we give them credit for. They animate the text. They bring the breath. “It’s all just black squiggles on a white page until someone reads it,” she says, paraphrasing Ursula K. Le Guin. This detachment allows her to receive criticism, and praise, with equanimity.

Some want more darkness. Some want less. “Some are your readers,” she shrugs. “Some aren’t.”

There is, in her attitude, a kind of spaciousness. The shrinking of ego. The growth of perspective. If Jenny had tried this at thirty-five, she admits, she might have crumbled under the industry’s contradictions. At sixty-five, she understands the absurdity of external validation. “I just write,” she says. “It’s in the DNA. Like eating. Or music. I don’t know how not to.”

And perhaps that is the most quietly radical thing about Jenny Dandy, not that she began writing late, but that she always knew she was a writer, even when no one else did.

Her books are not a bucket-list dream or a retirement project. They are what happens when the noise subsides and the voice returns. They are the echo of a life observed with patience, darned together with insight, and delivered not for approval, but because the time has come.

What’s next? The third book in the series, The Loft at Broadway and 14th comes out April 2026.