Hear the Conversation | Get the Book

The origin stories of private eyes are often tidy: a disillusioned cop, a case gone wrong, a woman in trouble. But for Stephen G. Eoannou, the creator of Nicholas Bishop—the stumbling, self-doubting, cane-wielding protagonist of After Pearl—the inspiration arrived in a haze of frustration, tempered by liquor and time.

The origin stories of private eyes are often tidy: a disillusioned cop, a case gone wrong, a woman in trouble. But for Stephen G. Eoannou, the creator of Nicholas Bishop—the stumbling, self-doubting, cane-wielding protagonist of After Pearl—the inspiration arrived in a haze of frustration, tempered by liquor and time.

“I was sitting at the bar, half-watching this detective flick on Netflix,” Eoannou recalls. “The guy was all charm and cleverness. I thought, ‘This guy wouldn’t last a day in Buffalo.’” He chuckles. “So I wrote the opposite.”

This act of contrarian creation, a kind of aesthetic rebellion, led him not to a clever plot twist but to a memory. Eoannou’s mind returned, unbidden, to a man his mother had known: Mickey Siki—“Siki” being Greek slang for insect. The name fit. “He was shifty,” Eoannou says, “weaselly.” The story, too, was odd: stranded in San Francisco during World War II, Siki was hit by a cab under circumstances murky enough to prompt lifelong speculation. Was it a drunkard’s misstep or a calculated bid for discharge?

“That’s my guy,” Eoannou realized. “That’s my detective.”

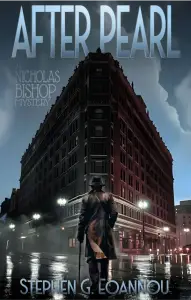

Thus emerged Nicholas Bishop—not so much born as limped into being. An alcoholic who may or may not have thrown himself in front of a taxi, Bishop wakes in After Pearl on the floor of his room in the Lafayette Hotel, a .38 discharged, the police closing in, and five days wiped clean from his memory. He’s broke. He walks with a cane. His dog has one eye and no known origin. He is, in short, a mess.

Set in wartime Buffalo, After Pearl opens not with a bang but with a hangover. Eoannou’s evocation of the city in 1942 is smoky and precise—ghosted by old diners, streetcar clang, the hum of radios reporting far-off battles. It’s a place where men vanish and women, like Bishop’s secretary Gia, pick up the slack and, often, the gun.

Gia, it turns out, was a correction. An agent, after reading Eoannou’s previous novel Yesteryear, which fictionalized the life of Lone Ranger creator Fran Striker, asked why there wasn’t a single strong woman in the book. “So,” Eoannou says, “I decided I’d give her one. And she’d be smarter than the guy she worked for.”

Gia is not the dame with a past, nor the blonde in trouble. She’s a sharp, competent, first-generation Italian American woman who keeps the story—and Bishop—on track. “She doesn’t need rescuing,” Eoannou says. “She does the rescuing.” His publisher was so taken with her that they asked for “more Gia,” and there’s already talk of a spinoff.

Eoannou writes like he renovates. Literally. He lives in a painstakingly restored Second Empire Victorian in Buffalo, and he applies the same obsessive attention to detail to his fiction. Dialogue comes first, usually—script-like and spare—then the world fills in. He cites Tobias Wolff’s metaphor about driving at night: you can’t see more than a few feet ahead, but you get there. “Only,” he adds, “I was driving blindfolded. And probably drunk. With the dog.”

The dog in question—a one-eyed mutt—belongs to Eoannou and appears in the novel. Like Bishop, the animal is worse for wear, and like Bishop, loyal in ways that defy logic.

The details are often personal. Tamis’s New Genesee Restaurant, a haunt in the novel, is named after Eoannou’s grandfather’s actual place, now gone, but memorialized in story and memory. Lefty the Dog Thief, another character in the book, was once a name whispered in family lore.

“I’m a seat-of-the-pants writer,” Eoannou says. “I don’t know what’s going to happen until it does. When Bishop was trying to piece together his lost five days, so was I. I didn’t outline. I just followed the ghost.”

This openness to uncertainty took time. For decades, Eoannou worked without publication, chipping away at stories that never saw print. That changed with Muscle Cars, his first short story collection, and Yesteryear, which won acclaim for its inventive take on radio history. But After Pearl, he says, is the book he most wanted to write. “During the pandemic, I wasn’t trying to write something commercial,” he explains. “I was just trying to escape.”

What emerged from that isolation is a detective novel about forgetting, remembering, and the way guilt calcifies into character. It is also, perhaps unintentionally, about Buffalo—the city that built Bishop and Eoannou alike, a place where hard winters sharpen memory and soften truth.

With a sequel, The Falling Woman, already slated for release in 2027, Bishop and Gia seem likely to return, continuing their uneasy partnership through the alleys of memory, war, and what noir does best: regret.

What does Eoannou hope readers find in After Pearl? “A good story,” he says. “Just that. A good story that takes you somewhere.”

And if it limps instead of struts, well—that’s the point.

Learn more about Stephen G. Eoannou.