Hear the Conversation | Get the Book

For Tom Epperson, the spark of creativity struck unexpectedly, as so many stories do, with a fleeting glance, a momentary interruption in the quiet rhythm of his life in Culver City, California. Pausing from his work on a novel, he sipped his coffee and gazed out the window. Through the thicket of shrubbery, he spotted a young woman jogging down the sidewalk. “She wasn’t running from someone,” Epperson recalls, but something in that brief flash ignited an urgent question in his mind: What if she’s the last female on earth and she’s being pursued by a pack of males? In the span of five minutes, the entire narrative of Baby Hawk unfurled before him.

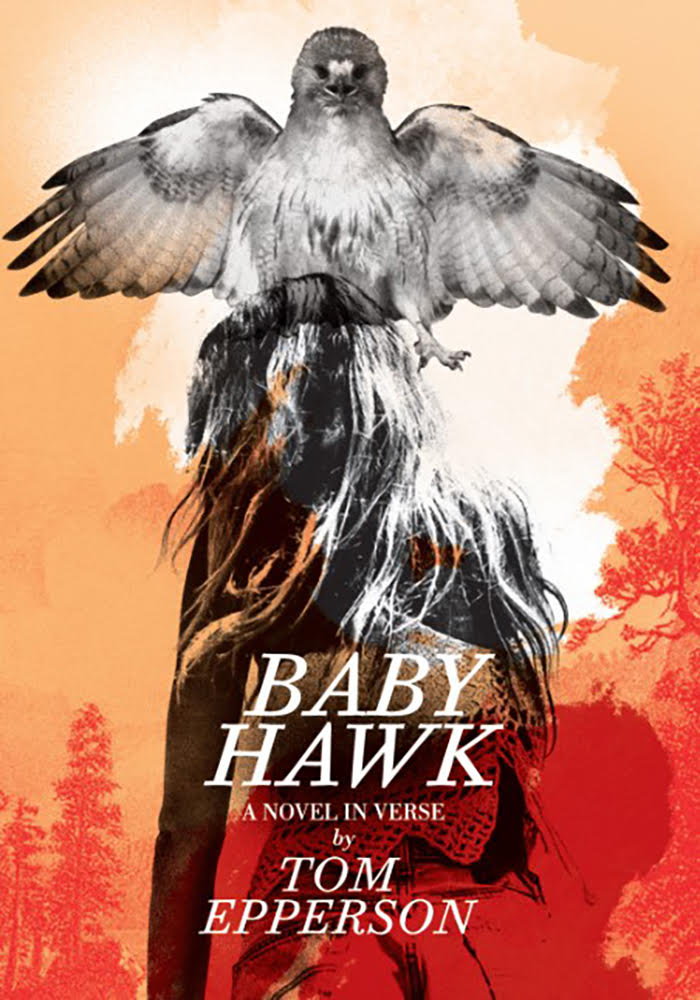

The novel that emerged from this fragment of an image is anything but the quiet meditation one might expect from a septuagenarian poet revisiting his roots. In fact, Baby Hawk is a visceral, high-octane novel in verse—a return to Epperson’s first love, poetry, a medium he abandoned for four decades. “I didn’t write a poem for 40 years,” he says, reflecting on his past as a poet in Arkansas before his career took him to Hollywood. “I always thought, maybe when I hit 70, I’d start writing poems again. And I did.”

Baby Hawk is the fulfillment of that promise, though it bears little resemblance to a soft, reflective rumination. Rather, it is a brutal, stripped-down narrative that offers no comfort to its readers. Set in a post-apocalyptic Northern California, the novel follows a seventeen-year-old girl, known only as “the female,” as she struggles to survive in a desolate world. She and her father live in isolation, until a band of sixteen “racist savage males” descends upon their lives, murdering her father and capturing her. These men see her not as a human being, but as a biological imperative—the Eve who must repopulate their ruined world. She, however, is “not real hot on that idea.”

In many ways, the female recalls another indomitable Arkansas creation: Mattie Ross from Charles Portis’s True Grit. Like Mattie, the female is “plucky and indomitable… tough and resilient.” Epperson, however, refuses to offer any details about her physical appearance, her name, the color of her eyes—her identity is defined entirely by her will to survive. “What she wants is to escape,” Epperson says. “And that’s the setup.”

What’s striking about Baby Hawk, besides its brutal subject matter, is the form Epperson chose. A novel in verse might conjure expectations of lyrical meanderings or introspective musings, but Epperson’s four decades as a screenwriter have indelibly shaped his narrative instincts. “To write a movie, it’s a very stripped-down process. You have to keep things moving,” he explains. Epperson subscribes to a screenwriting adage that no scene should run over four pages. “Basically, it’s a propulsive, forward-moving thing. And so actually Baby Hawk to me is more like a screenplay than it is like a novel.”

The novel’s free verse is lean and muscular, unburdened by rhyme and meter, propelled instead by the rhythm of plot. The lines break like quick cuts in a film, pushing the reader forward with each turn of the page. “Just read two or three pages,” Epperson assures potential readers who might be skeptical of the format. “You’ll forget it’s a poem. It’ll just be a story.”

The fusion of cinematic pacing and poetic form creates a narrative that occupies the charged space “between horror and hope,” as one interviewer aptly put it. Epperson agrees: “A lot of my stuff is a mixture of hope and horror.” He points to One False Move, the 1991 film he co-wrote with Billy Bob Thornton, which, though violent and shocking in its opening scene, was also laced with humanity and humor. “That’s how life is,” he insists. “You go to a funeral for your best friend, and then you’re laughing at some point. You don’t curl up and die because something horrible happens. You keep going.”

This perspective, Epperson’s belief in perseverance amidst suffering, is informed by his own life, a life that has demanded resilience at every turn. He speaks of his early years, when he was “nothing” at twenty-four, sleeping on his mother’s couch, and not selling a script until he was thirty-six. When he hears a young screenwriter complain, “It shouldn’t be this hard,” he unleashes a small, exasperated rant. “Holy crap. You need a reality check. Hollywood’s always been impossible to break into. Yes, ma’am. It’s hard. It’s always been hard.”

The theme of life’s hardness, and the ever-present specter of its end, is a pervasive preoccupation in Baby Hawk. Epperson, who has just completed a 668-page novel about the world’s collapse, is not shy about his pessimism. “I think we’re on the way to civilizational collapse,” he says flatly. He lists climate change, deforestation, and war as the key drivers of this impending downfall, lamenting humanity’s fundamental misunderstanding of its place in the world.

He dismisses the Biblical fantasy of man’s dominion over nature, seeing it as a root cause of humanity’s destruction. “Humans are animals, and they don’t realize it,” he asserts. “They think there’s no limits.” He is particularly scornful of the recent proposal to build a nuclear reactor on the moon while Earth burns. “We need to get a grip,” he says, shaking his head. “We are ruining everything.”

In contrast, the protagonist of Baby Hawk represents a simpler, more harmonious relationship with nature. “She’s woman nature,” Epperson explains. “She’s happy in the forest. She loves all the creatures. She’s the way I wish everyone was.”

In Baby Hawk, Epperson has crafted a brutal fable for a world on the brink, an exploration of humanity’s relationship with nature, survival, and the unyielding will to live. Born from a fleeting image, filtered through the lens of a screenwriter’s discipline, and powered by an urgent, primal fear for the future, the novel is a story about the birth of a new world—a terrifying and timely one. As Epperson returns to poetry to tell it, we are reminded that sometimes the most profound myths are born from the harshest realities.