Hear the conversation | Get the Book

It is a curious feature of counterfactuals. The grandest ones, a different victor in a war, a spared president, often feel the most remote, their consequences unfolding on a scale too vast for the human imagination to properly map. The true tremor of an altered past is felt most keenly not in the tectonic shifts of geopolitics but in the near field, in the subtle warping of the cultural atmosphere. What of the gossamer stuff, the half-remembered lyrics and boardwalk mythologies that constitute a nation’s private folklore? It is this more intimate brand of historical inquiry that animates

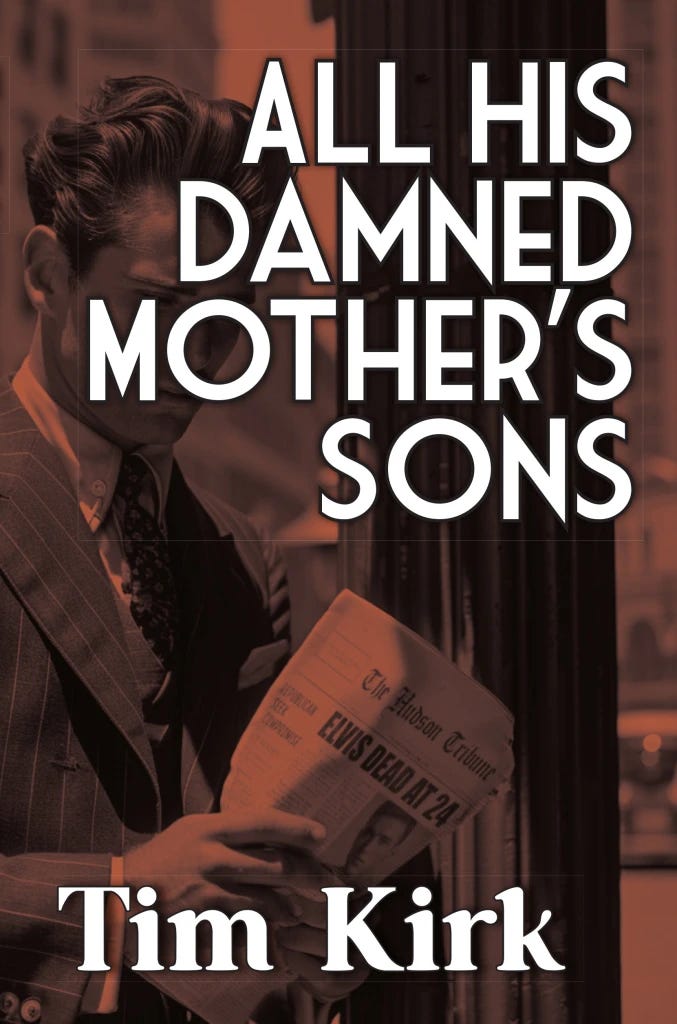

Tim Kirk’s new novel, All His Damned Mother’s Sons, begins with an absence so bright it casts its own light. The premise is deceptively simple: during his Army service in Germany, Elvis Presley dies. The world does not stop. No treaties are unwritten, no rockets fall from the sky. And yet, back in the ad hoc country where jukeboxes and hucksters hold equal tenure, a vacuum has opened in the shape of a pelvis, and a generation must learn to hum a different tune.

The effect of this subtraction is not societal collapse but a series of quiet derangements, tracking four young men as their lives veer onto harsher roads. A decade’s worth of choices, honky-tonk bookings, petty scams, bargains struck on a battlefield, accrue into a reckoning.

Tim has constructed a noir road story that doubles as a cultural X-ray, a guided tour through the undercarriage of postwar ambition and the stubborn glamour of the American outlaw. He writes with the coiled posture of a man who has spent a lifetime trimming dialogue until it clicks. A veteran screenwriter, Tim speaks of the form with the fond exasperation of a watchmaker discussing a particularly finicky escapement: the action lines like haiku, the dialogue forced to bear the full weight of narrative momentum.

He recounts a quintessential studio anecdote, an executive insisting on the removal of a running gag that a producer had once demanded be inserted, that serves as a parable for the ways in which both jokes and visions can be sanded into compliance. That long apprenticeship in “notes,” he suggests, instilled an instinct for structure and compression. The novel, then, arrived as a kind of release. Once you have mastered the placement of the bones, you are finally free to choose the flesh.

The novel’s inciting spark, as it happens, was not the missing King but a kid with a guitar. Billy Clover, one of the story’s central figures, first appeared in Kirk’s short fiction, a Griffith Park stray with a vocabulary steeped in Western swing and a nascent itch for rock and roll. But to give a character like Billy a trajectory that could bear the freight of a country’s inchoate hunger, Tim understood that he would have to remove the gravitational body around which so much of mid-century popular music orbited. “You just can’t do that if Elvis is alive,” he tells me, with the practical ruthlessness of a novelist who treats history as a set of levers to be pulled.

In the world that results, the machinery of fame doesn’t cease; it merely recalibrates. Money men hunt for the “next Elvis,” a phrase that operates as both a commercial directive and a kind of curse. One of the book’s distinct pleasures is watching the talent factories of the era, the radio programmers, the promoters, the colonels of dubious provenance, spin on without their lodestar.

Tim renders this period not only through his characters’ arcs but through a kind of narrative archaeology. He salts the book with ephemera, imagined squibs from TV Guide, fabricated clippings from an early Rolling Stone, a Zappa sighting or two, until the reader begins to feel the paper texture of the time. The result is less alternate history than alternate atmosphere. The effect is one of subtraction; you keep noticing what isn’t there, the way a familiar harmony sounds when one voice falls silent. Tim’s restraint is precisely the point. This is not some grand “Man in the High Castle” thought experiment, with its attendant geopolitical aftershocks; it is a neighborhood study of cultural weather. The storm happens offstage. His characters, unknowing, simply live inside its changing pressure.

The title itself is salvaged from a different precinct of the American myth. Tim recalls chasing a phrase that had lodged in his head, “mother’s sons”, before locating its lineage in a threat delivered by John Wayne. The words carry a certain gunsmoke bravado, a moral roughness that migrated from frontier fantasies into the crime pictures of mid-century and back again. It is a fitting banner for a book that takes the romance of outlawry seriously without ever romanticizing its costs. The nineteen-sixties, in this telling, are not a montage of hallucinatory liberation but a long corridor of transactions and performances, the last years when a handshake in a back room could still forge a national star. As to why that decade refuses to recede, why its melodies continue to sell us trucks and insurance, Tim positions himself not as a cultural theorist but as a witness; he feels the spell, and does not pretend to possess the counter-charm.

On its surface, the narrative splinters: one boy pursues music, another succumbs to a life of crime, a third goes to war, and a fourth learns how quickly ideals can curdle under the fluorescent lights of bureaucracy. Yet the book’s deep subject is the nature of survival, how it is chosen, how it is rationed, and who pays the bill when luck runs out.

Over ten years, the four threads pull tight, snapping together in a final showdown that feels both hard-won and brutally inevitable, the sort of convergence that noir promises and life rarely delivers. What ultimately unites these men, Tim suggests, is less a sense of brotherhood than a shared bewilderment at the road they have traveled. In their own distinct keys, they are all asking the same question: When, exactly, did I become the man I am?

One can trace a credible lineage for Tim Kirk’s prose. There are echoes of Jim Thompson’s moral sinkholes and James Ellroy’s tabloid orchestrations, of Raymond Chandler’s silken contempt for civic hypocrisy and Shane Black’s magnesium-bright patter. But Tim’s own voice is gentler, more attuned to the grain of memory. He is a devoted reader of police procedurals, particularly those written by active detectives, admiring the way that method becomes narrative, how sheer repetition, knocking on another door, asking the same question, builds its own unique suspense. Raised in Los Angeles, Tim recognizes the city’s social archetypes. He writes the party-boy psychopaths, the strivers with good hair and anemic impulse control, with the casual familiarity of a local pointing out landmarks.

For all its gunmetal sheen, however, the book is shadowed by a quiet dedication. Tim mentions that fatherhood shaped his earlier work, Burnt, a triptych of mothers and daughters across three eras; The Feral Boy Who Lives in Griffith Park, written in the interludes of playground naps. This novel, he allows, bears the imprint of a friend, Josh, an audacious screenwriter who died before he could read the finished manuscript. Josh’s sensibility, his taste for the unruly, his disdain for the timidly plausible, haunts certain scenes like a sly grin. There is a cathartic bout of righteous destruction that feels staged precisely to make him laugh. The elegy is never declared; it is felt as velocity.

If All His Damned Mother’s Sons argues, subtly, that to remove a signal artist from the record reshapes not only the playlist but our very sense of what a life in music can look like. Tim admits to an unfashionable affection for the late-period Elvis, the Vegas years, with all their attendant bombast and sweat, and part of the novel’s ambient charge is its recognition that erasing such a figure subtracts not just the early hits but the later, more complicated evolutions.

In this telling, a grief for what never happened sits right next to an appetite for what still might. Tim’s day job taught him to keep the camera moving, and his novel wisely refuses the tidy nostalgia of a greatest-hits compilation. It is a long drive on bad roads, with flashes of beauty in the rearview mirror and a destination no one quite believes in until the moment of arrival.

The King is gone. The hustlers keep hustling. The outlaws are still rehearsing their reasons. What remains, in Tim Kirk’s resonant pages, is the sound of invention under pressure. It is the music a country makes when the note it expects doesn’t come, and the machine is forced to sing anyway.