Hear the Conversation | Get the Book

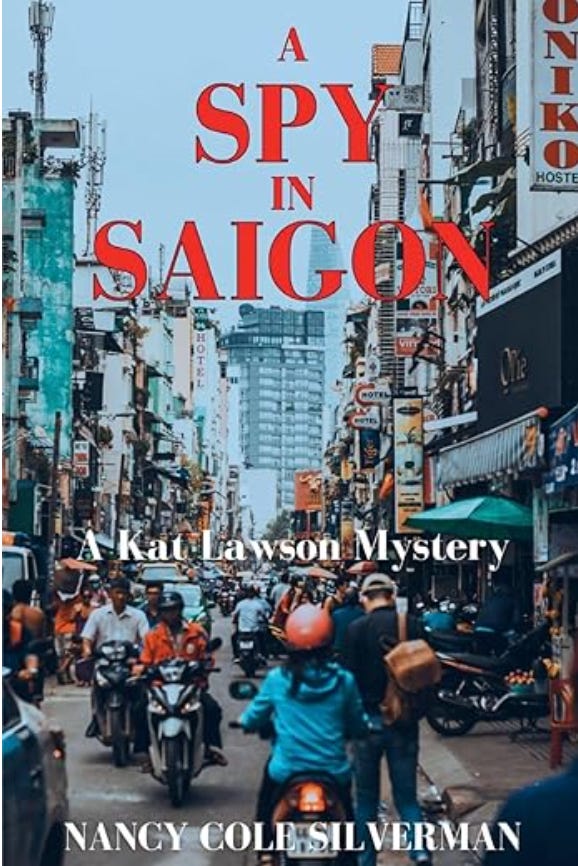

With A Spy in Saigon, Nancy Cole Silverman steps into the shadowed territory of the Vietnam war, returning readers not to the jungle or the battlefield but to the uneasy aftershocks that reverberated through kitchens, base housing, and the liminal space between survival and denial.

Her protagonist, Kat Lawson, is a heroine assembled from the spare parts of mid-century American reinvention. Once a newsroom casualty, toppled by the kind of scandal that was less an aberration than an occupational hazard, Kat now threads the blurred line between journalism and espionage. She has been quietly conscripted by a government operation masquerading as an innocuous travel magazine, Journey International. A courier with a reporter’s instincts, she is valuable precisely because she is ordinary. She is also expendable.

The ostensible assignment is tidy enough to slip past suspicion: fly to post-war Vietnam, file a breezy feature, and hand off a small cache of passports and cash to a defecting informant. But Nancy, a veteran of journalism and of the Vietnam era’s domestic toll, knows that neat narratives belong exclusively to those far from the blast radius. The mission, inevitably, unravels. Kat finds herself tracked by a predator who seems to anticipate her movements with unnerving intimacy.

What lifts A Spy in Saigon beyond the scaffolding of a conventional thriller is the unmistakable tremor of lived memory. Nancy was an Air Force wife during the war, one of the women whose emotional geography rarely appears in literature. In conversation, she admits that the memories resurfaced with an almost involuntary force. “I had tucked those stories away,” she says. “And then they came back.” Her research, in this sense, is less archival than autobiographical: the silent treaties among “waiting wives,” the admonition to remain apolitical lest one jeopardize a husband’s assignment, the black MIA flags that fluttered like public declarations of private dread.

In the Johnson years, military life was engineered to keep women in a state of exquisite dependence. Wives without Power of Attorney could not access bank accounts or information. Rumors circulated faster than official communiqués. Support systems had to be improvised: co-ops, whispered conversations, an underground of emotional first responders. You feel that inheritance in Kat, her hesitations, her heightened radar for danger, her slow hardening into someone who can no longer afford to be naïve.

Nancy traces this evolution with the quiet patience of someone who has lived it: Kat, once a “rejected reporter,” emerges as a woman unafraid to “step out,” no longer buffered by the suburban rituals of malt shops and Friday night football. If the first books charted her reassembly, this one captures her recognition that freedom, personal or political, is never free of collateral damage.

Threaded through the plot is a darker, contemporary resonance: the trafficking of children in the post-war vacuum, a black market made more volatile by geopolitical disarray and the collapse of Soviet influence. Nancy approaches the subject with a blunt clarity. Children of American GIs, she notes, were particularly vulnerable, “easily fed, easily traded.” The novel refuses to let that exploitation fade into the fog of historical abstraction. It becomes the engine of Kat’s moral acceleration.

Writing the book, Nancy confesses, demanded a kind of excavation she wasn’t sure she had the right to undertake. She was, in her words, “a little afraid” to write it. But fear, she suggests, is the muse that matters. “You have to write from the gut,” she tells other authors, a dictum she follows here with conspicuous fidelity. The narrative pulses with the unease of someone dredging up truths that resist simplification.

In the end, A Spy in Saigon is not merely a chase through tangled alleys and diplomatic no-man’s-lands; it is a meditation on American responsibility, what we promise, what we abandon, and what we inherit from the conflicts we export. Nancy hopes readers come away with a simple, if sobering, recognition: that freedom extracts a price, and that citizenship requires a kind of moral bookkeeping we too often avoid.

Kat Lawson’s newest outing is a reminder that the most indelible mysteries are not the ones solved by clever deduction, but the ones that force us to confront the unspoken debts of history. Nancy Cole Silverman has crafted a novel that is both taut and tender, a spy story that carries the weight of an unwelcome truth: some wars refuse to end just because the world has stopped watching.