Hear the Conversation | Get the Book

In the kitchens of Incheon’s Chinatown, there exists a cuisine that defies nomenclature. It is neither quite Chinese nor fully Korean, yet it is devoured with the cultural ease of pizza in American suburbs. Its staples, jajangmyeon, noodles lacquered in inky black bean sauce, and tangsuyuk, a sweet-and-sour pork rendered in a translucent glaze rather than the more familiar sticky syrup, tell a story not of fusion but of survival. They belong to ethnic Chinese families who held no Korean birthright citizenship, could not vote, and were long barred from owning land. Their food evolved in the spaces they themselves were forced to occupy.

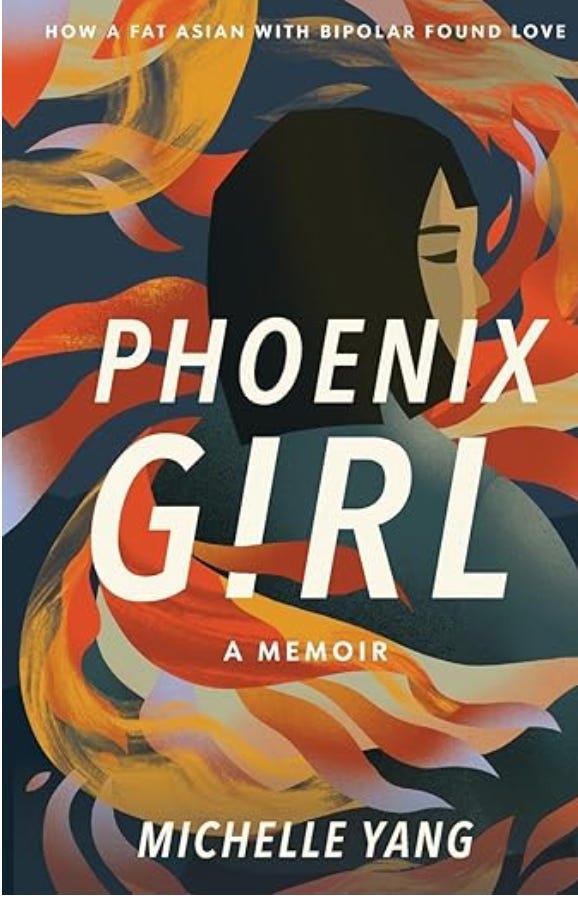

From this in-between world comes Michelle Yang. Her memoir, Phoenix Girl: How a Fat Asian with Bipolar Found Love, charts a life defined by thresholds, of identity, geography, and the mind itself. Her story begins not with arrival but with suspension: a ten-year wait as her family’s immigration petition sat stalled in bureaucratic amber. Her parents applied to leave Korea in 1980; approval arrived only in 1990, when Michelle was nine. The family exchanged their stateless existence for the sunburnt vastness of Phoenix, Arizona, where the promise of the “Golden Mountain” materialized not in opportunity but in and the fluorescent-lit confines of a Chinese takeout restaurant. By twelve, Michelle was stationed at the register, perfecting the calculus of customer service while navigating the volatility of a father whose dominance shaped every aspect of home life.

In many immigrant narratives, the trope of the “model minority” functions as aspiration. For Michelle, it functioned largely as camouflage. Straight As, debate club, endless extracurriculars, these were not simply achievements but shields, disguising a private realm that was beginning to splinter. “My parents regarded it with a lot of shame and stigma and denial,” she says of her early mental health struggles. Teachers, conditioned to read academic success as emotional stability, misdiagnosed her distress. It is a statistical illusion particular to Asian America: one in four people worldwide will experience a mental or neurological disorder, yet stigma in Asian immigrant communities, like many others, suppresses diagnoses, obscuring the suffering of those who excel until they collapse.

Michelle’s collapse arrived with tragic symmetry. During a study abroad semester in her ancestral land of China, the ancestral homeland she had known mostly through food and fragments, she watched the Twin Towers fall on a dormitory television. The geopolitical shock was immediate, the psychological quake, more subtle. “It took a few days to manifest,” she says. The isolation of being abroad, far from home and language, propelled her into a psychotic break. In China, she finally became visible not as a prodigy but as a patient. The diagnosis: Bipolar Disorder.

Recovery, she notes, is not a rebirth but a convalescence. “It is like having surgery,” she says. “When you come out, you need a recovery period.” But her prognosis from family members landed closer to fatalism: no degree, no career, no marriage, a life reduced to the management of illness rather than the pursuit of fulfillment.

Michelle refused the limitation. She earned an MBA, built a corporate life in Seattle, and rose through the ranks until, one afternoon, she found herself crying at her desk. Her department had been sold off; her hidden condition felt like contraband. The dissonance between her internal landscape and her external résumé had become untenable. At 36, she realized she was still living for a father whose approval she had outgrown, a man who no longer dictated her future.

Phoenix Girl is Michelle’s intervention in the absence she once faced. It is a book addressed, implicitly, to her twenty-year-old self, the young woman searching library shelves for someone who looked like her, lived like her, struggled like her, and survived. Michelle refuses the sensationalism that often accompanies mental health narratives. “The only people you see in the media are those in crisis,” she points out. The high-functioning many, the ones raising children or leading teams or writing books, remain largely invisible, managing shame as vigilantly as symptoms. The result is a “Catch-22 of stigma”: silence begets erasure. Erasure reinforces shame.

Today, Michelle’s rebellion is modest in its gestures and radical in its implications. It takes the form of meals shared at a kitchen table, where Mapo Tofu is served not as a nostalgic artifact but as a reclaimed inheritance. It looks like teaching her twelve-year-old son that emotions are not shameful but nameable. It looks like acknowledging the pain that shaped her without allowing it to dictate her future.

Michelle Yang has moved from the fluorescent anonymity of the takeout counter, to a life defined by nourishment. Her memoir is not simply a record of survival. It is a testament to reclamation: of voice, of identity, of the right to one’s own interior life. In breaking the cycle of silence, she has done what her ancestors’ cuisine long attempted, created something whole from the fragments of a life lived between worlds.