Hear the Conversation | Get the Book

Gil Gillenwater is a real-estate man with a desert tan and a taste for Harley-Davidsons. He likes to summarize his personal philosophy in the sort of bumper-sticker maxim that would look right at home on a chrome tailgate: He who dies having had the most fun wins.

It’s a declaration that invites a raised eyebrow, particularly when uttered by someone who has spent the better part of forty years engaged in cross-border humanitarian work. Yet in Gil’s telling, fun is not merely compatible with charity; it is the engine that keeps the whole enterprise roaring.

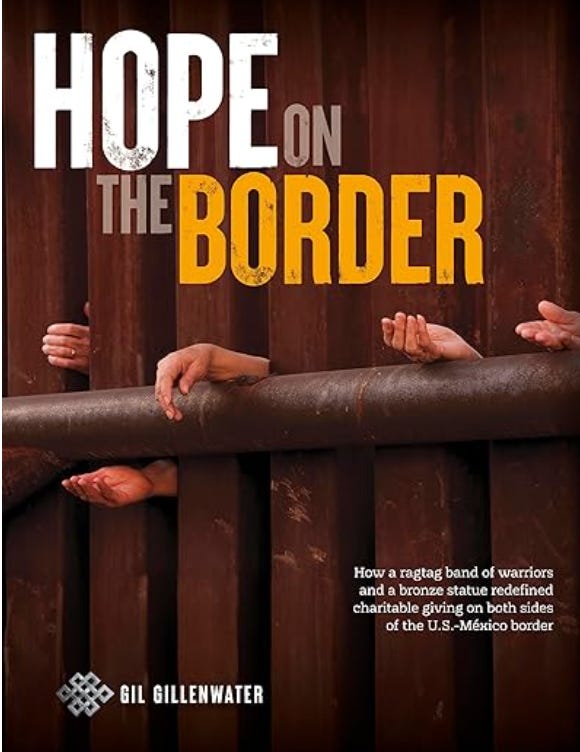

“I swore when I started that I would do this as long as it’s fun,” he says. “And for forty years, it’s been an absolute blast.” For Gil, the border’s scars, its contradictions, its ceaseless churn of seeking and suffering, has provided not just purpose but exhilaration. His newly published Hope on the Border is less a memoir than a manifesto: an argument that altruism has been sabotaged by its own PR.

“Somehow charity got a bad rap,” he says. “Jesus hanging up on a cross” depiction of noble self-denial. “Sacrifice is grounded in lack.” Americans, he believes, have been sold the wrong story, one of grim duty and leftover time rather than joy. It’s not that he wants to remove morality from giving; rather, he wants to replace its martyrdom with mutual delight.

He calls this arrangement “reciprocal giving”, a spiritual exchange rate in which “we feed their stomachs, they feed our souls.” Years ago, deep in Mexico’s Copper Canyon, he gifted a handsome knife to a young Tarahumara runner, only to later find it discarded on a log. A local elder explained the oversight: a gift that cannot be returned is not generosity but humiliation. Gil learned how the impulse to give, pure in intention, can flatten a human relationship into a hierarchy.

Dignity became doctrine. On the border, where Rancho Feliz now distributes a thousand bags of food in a day, he noticed a familiar posture: heads bowed, shoulders drawn inward, eyes cast down. Supplicants. “I thought, I’m violating my own principle,” he recalls. The solution was as local as it was symbolic. In Agua Prieta, where plastic bags bloom like an unofficial national flower, someone receiving a bag of food must first collect twenty pieces of trash. “Look at my bag, two hundred pieces!” one woman announced, triumphant. The line straightened. Pride reappeared

This is Gil’s gospel: half Buddhism, half capitalism, the cross-border sutra of a man who has meditated for decades yet retains the deal-making instincts of a real-estate developer. He likes to describe his approach as “enlightened self-interest.” It is in my benefit to help you, he insists, because in helping you, I help myself. His frustration with America’s “incorrigible fixation on the vertical pronoun – I” is punctuated with statistics delivered like punchlines. “Do you know what this country spent on pet clothing last year?” he asks, incredulous. “Two billion dollars. That’s seven million years of Rancho Feliz-funded high-school education.”

It’s a sharp indictment, one that becomes even more complicated as it collides with the material reality of the border itself. Four decades of proximity to the gates of the world’s wealthiest nation have left him unimpressed by ideological purity and deeply wary of romanticized openness. “Thirteen million people poured through our borders, unvetted,” he says. The humanitarian, it turns out, favors a process where immigrants are welcomed but citizen ship is earned.

His argument is less about fear than arithmetic. Forty-four percent of the planet lives on less than seven dollars a day. “America can’t take that burden on,” he says. “In the twenty-first century, your solution is to build a wall?” he asks, then shrugs. He proposes a ten-year path to citizenship for those already here, paired with a $10,000 fine. “What’s twenty million times ten thousand? A home run.”

Gil’s volunteer complex in Mexico boasts comforts that “would rival any hotel in Phoenix,” because wealthy donors do not want to sleep on gym floors. He isn’t in the business of shaming the affluent into virtue; he is in the business of tempting them. “Taste it, feel it,” he urges, addiction as civic engagement.

Under Gil’s rules, the $2 billion spent on dressing pets would not merely be a sin of frivolity; it would be a catastrophic failure of imagination. There’s more thrilling fun to be had, fun that looks suspiciously like compassion.

And for Gil Gillenwater, that thrill remains the point. The border may be his mission field, but joy is his measure of grace. He is, in his own unapologetic formulation, a selfish-salvationist: a man who believes that the shortest route to personal enlightenment might just be through somebody else’s full stomach.