Hear the Conversation | Get the Book

In the sprawling, fluorescent amphitheater of contemporary medicine, the neurologist inhabits a haunted corridor. It is a discipline less enamored of the decisive fix than of long, persistent detective work. It can be a Sherlockian pursuit in which clues arrive as tremors, hesitations of gait, half-formed memories, or the subtlest of ocular betrayals. For Dr. Carolyn Larkin Taylor, who has spent decades patrolling this fault line between biology and the ineffable, the most indispensable diagnostic instrument is not the reflex hammer tucked into her coat pocket, but the ear.

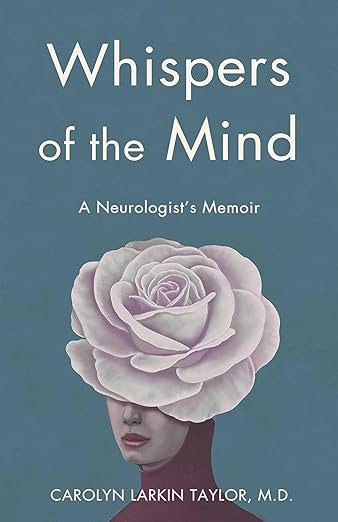

“I’m an introvert, I’m a listener,” Dr. Taylor says with the kind of self-possession that feels earned rather than performed. That quiet attentiveness serves as the tuning fork for her new memoir, Whispers of the Mind: A Neurologist’s Memoir, a book assembled not from the polished routes of grand rounds but from the furtive, late-night scribblings of a doctor coping with the emotional hydraulics of her profession.

Her path to neurology was neither direct nor predestined. Dr. Taylor began in optometry, content with the orderly geometry of vision, until a colleague offered her a piece of existential arithmetic: she would turn forty regardless, why not turn forty as a physician? It was advice half-flippant, half-prophetic. She entered medical school imagining a future in ophthalmology; the eye was her native terrain. But the monotony of cataract surgery left her unmoved. The nervous system, by contrast, exerted a gravitational pull, “like a magnet,” she recalls, a seduction rooted in its impossible entanglements, its fusions of psychology and physiology; its demand that a clinician be equal parts scientist, detective, and confessor.

Because of her origins in eye care, Dr. Taylor soon found herself a refuge for patients with Multiple Sclerosis, a disease that often announces its arrival in the optic nerve. Unlike surgeons who repair a joint and wave their patients back into their lives, Dr. Taylor discovered that neurologists enter sometimes lifelong relationships with those they treat. “We don’t have a cure,” she says, with a pragmatism bordering on tenderness, “but we can hold people’s hands.”

Whispers of the Mind chronicles this handholding, but also the tremor in the physician’s own. The memoir’s stakes lie not only in describing neurological catastrophe, but in undressing the profession’s emotional exoskeleton. Dr. Taylor writes of the psychic burden of declaring a teenager brain-dead, of the macabre choreography that precedes delivering an ALS diagnosis, waiting for the patient to speak the unspeakable so she does not have to.

But the book’s emotional fulcrum is the death of her mother. It happened four weeks into Dr. Taylor’s neurology residency, a massive intracranial hemorrhage, made worse, she suggests, by the casual dismissal of an older woman’s complaints. She returned to work five days later, bruised by grief and protocol, and was promptly berated by an elderly man demanding a male doctor. Her composure cracked. She retreated to a hospital restroom and wept, her own white coat suddenly absurd against the enormity of personal loss. She later apologized to the man, who accepted, but the rupture lingered. For months, every older woman in the ICU bore her mother’s face.

This collision, between the distance required to function and the intimacy required to heal, is the book’s animating tension. Dr. Taylor wrote at night, alone in the quiet house while her husband and young son slept, trying to metabolize the days spent in inpatient neurology, a realm she describes as “death, overdoses, strokes.” These were not merely medical events; they were the accumulations of human grief which fill the invisible wheelbarrow we humans push when circumstance prevents us from processing our own feelings in real time.

And yet, for all the bleakness she has witnessed, Dr. Taylor remains a cautious optimist. She speaks with a kind of tempered delight about neuroplasticity, about the elegance of Tai Chi, about glimmers of hope in Alzheimer’s research. For her, the brain is not a doomed organ but a mutable landscape, a terrain that can be rehabilitated, even gardened.

Ultimately, Whispers of the Mind argues for the narrative heart of medicine, the belief that stories exchanged across exam tables and hospital beds are not distractions from clinical work but the work itself. “At the end of the day, it’s the true stories,” Carolyn Taylor told me. “It’s what makes us feel like we are all part of one common humanity.”

In her telling, the neurologist is not simply a custodian of the nervous system. She is a witness to the fragile, ongoing courage required to live inside one.