Hear the Conversation | Get the Book

In the Bighorn Mountains of Wyoming, the land does not simply sit there looking photogenic. It behaves. It asserts itself with the sort of impersonal authority usually reserved for weather systems. Pamela Fagan Hutchins, who lives in this high-altitude country with a degree of practiced distance from modern conveniences, describes the place with the steady realism of someone who has watched beauty turn, without warning, into a problem. In her view, the landscape is not a backdrop so much as a co-conspirator, a vast mechanism of rock and sky that can make a person feel small and then make them pay for it.

Pamela is a USA Today bestselling novelist with more than three million books in print, which is the sort of statistic that feels slightly surreal when you imagine it paired with a life lived semi-off the grid, among pines and switchbacks and long distances between errands. Still, the combination makes sense. Her work depends on consequences. The mountains provide them naturally. They offer an atmosphere in which a wrong turn can become a narrative, and a secret can feel as heavy as an oncoming storm.

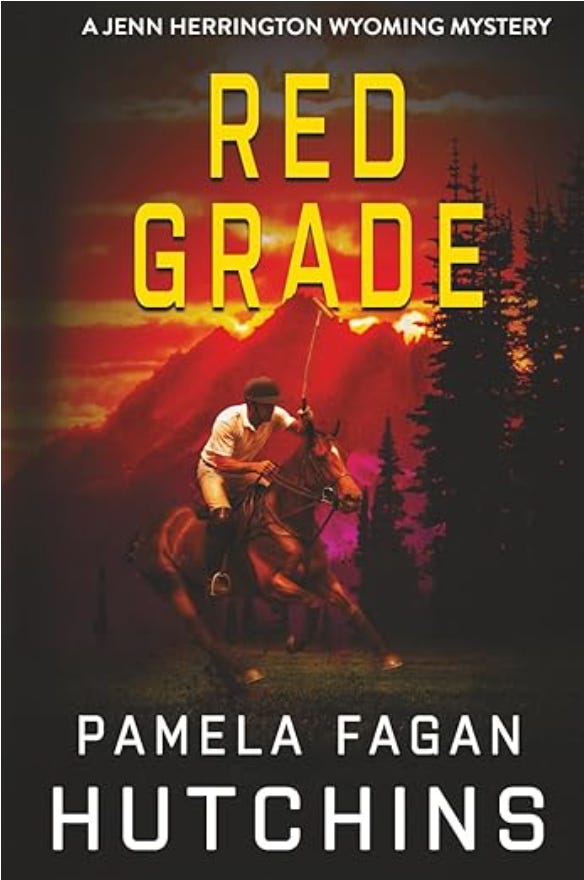

Her latest novel, Red Grade, the third installment in the Jenn Herrington Wyoming Mystery series, arrives carrying a surprising accessory, polo mallets. It is not the first time a crime novel has wandered into an elite sport for the purpose of exposing its private rules. But imagine polo transplanted onto the dust and grit of the mountain West. The sport belongs to the manicured confidence of East Coast wealth, to the kind of leisure that requires staff, horses, and an assumption that you will be treated gently by the world. Wyoming, by contrast, has never made much of a promise to be gentle.

And yet Pamela insists that the sport is there, quietly. In summer, teams that winter on the East Coast descend on the Big Horn area, bringing equipment, horses, money, social choreography, the sheen of polished leather. Wherever wealth gathers in close quarters, the old temptations follow, and the peculiar insulation that comes from knowing consequences is often negotiable. “With money and with power and with something sexy comes the opportunity for a nice juicy murder,” Pamela says. In Red Grade, the collision becomes literal when a celebrated player dies in the middle of a match, an event initially framed as an accident, until the narrative begins to insist, it is not.

The novel has been described as “Nora Roberts meets Yellowstone,” a formulation that Pamela seems to accept with good humor. It suggests a blending of romance and threat, emotional intimacy with environmental menace, the soft and the hard stitched into a single garment. The Bighorns lend the story what Pamela calls the “land-may-kill-you” quality, a sense that danger is not always a villain in human form. At the same time, polo offers a closed ecosystem of privilege, a small society with its own signals and silences, its own methods of keeping outsiders outside.

This is, for Pamela, part of the appeal. It is a community in which reputations matter, discretion is currency, and the people involved can afford to arrange their own versions of reality. “They have the money to get away with things,” she observes. “And because so few of us actually get to peek inside it, it’s really rich with intrigue.” The phrase “peek inside” has the quality of a dare, as if the act of looking is itself a form of risk.

Her protagonist, Jenn Herrington, has a biography that grazes close to the author’s. Harrington is a lawyer who finds herself pulled back into legal conflict against her better judgment, and she is also a writer of mysteries. But Red Gradesharpens the tension by making the case personal. The investigation begins to circle Herrington’s husband, forcing her into the private terror of professional duty colliding with marital loyalty. The procedural mechanics are still there, the interviews, the evidence, the inevitable narrowing of possibilities. But they are threaded through something more intimate and destabilizing: the question of what you do when the person you have built your life beside becomes the person you might have to confront.

Pamela has said she enjoys a good police procedural but prefers one in which the investigator has “a lot of skin in the game.” Her choice allows her to examine the anxiety that sits beneath long-term companionship, the quiet dread that intimacy does not always guarantee knowledge. The fear is not only that your partner has secrets, everyone does, but that the secret might be catastrophic, and that you might be the last person to see it coming.

For all the melodrama inherent in the genre, Pamela is careful about the bones of reality. Her fact-checking system involves the police chief of Sheridan, Wyoming, Travis Koltiska, who serves as a kind of practical anchor. His approach, she suggests, is not to bury the narrative in technical procedure, but to keep it accurate and efficient. The details should be right, but they should not slow the book down. “We want it to be improbable, but still possible,” Pamela says. It is an author’s tightrope, the balancing act between what a story wants to do, and what the world would actually allow.

Her own history as a novelist is tied neatly to her marriage. Pamela has described her husband, Eric, as the person who discovered her secret writing and pushed her to publish. At the outset, he acted as a “translator for a love language” she had not yet fully learned. The phrase is striking because it frames encouragement as intimacy, publishing as something akin to being understood. It also helps explain why Pamela’s books resist the sterile pleasure of the purely intellectual puzzle. She is drawn instead to narratives crowded with relationships, full of the soft complexities that make a crime feel less like an abstract event and more like an injury to a community. “I don’t think I enjoy a story that doesn’t have the full breadth of human relationships in it,” she says. “Where’s the real part?”

These days, Pamela writes from the road as often as she does from her mountain home, drafting between catamaran trips and hiking expeditions, building sentences in motion. It is the sort of lifestyle that sounds whimsical until you remember the discipline required to make it productive. But whether she is working from somewhere in Europe or from the Bighorns, her attention stays trained on the American West, on its open skyline and tightly wound communities, on the way freedom can resemble solitude, and solitude can resemble peril.

In Red Grade, the mystery is not only who committed the crime. It becomes a case study of how much of another person can ever truly be known, even after years of shared life. It is a noir sentiment, dressed in Wyoming light.

Pamela Fagan Hutchins, who speaks often of relationships and the possibility of doing better within them, offers her lesson with a novelist’s dark practicality. Sometimes the most instructive scene is the one in which the glass house shatters, and we have to stand in the debris and decide. What we are willing to believe about the people we love?