Hear the Conversation | Get the Book

In mid-century Philadelphia, before backstage access required a security badge and a retina scan, there existed certain portals through which a determined teenager might slip. The stage door of the Academy of Music was one such loophole. Through it, Nancy Shear, fifteen, besotted, and desperate for escape, began a lifelong occupation of the orchestral world.

Nancy’s infatuation was not merely musical. “I came from a very difficult home life,” she says now, her voice softened but not detached by the sixty intervening years. The orchestra, to her, was less an institution than a chosen family: professionals united not by blood but by devotion. The sounds themselves, strings, brass, that impossible shimmer of a collective breath, offered what she calls “the great expression.” But it was the presence of those who made them that felt like sanctuary.

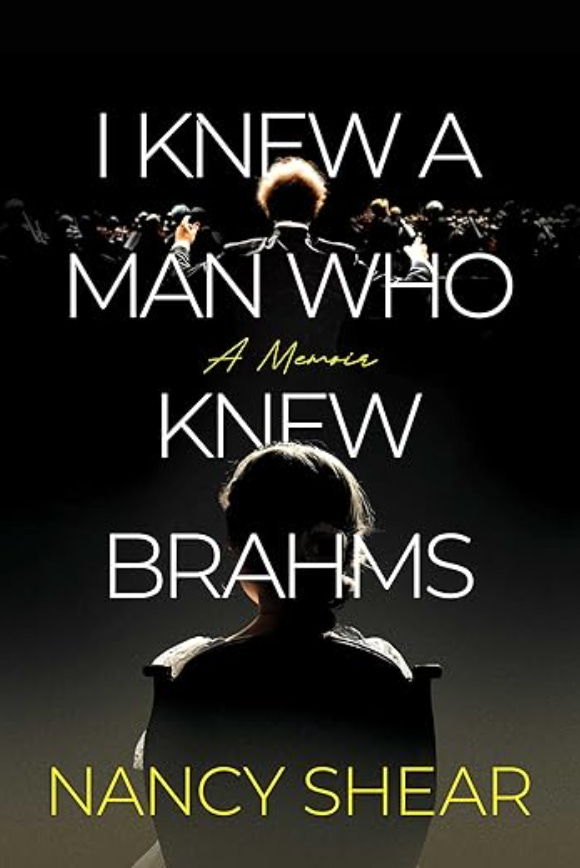

Her memoir, I Knew a Man Who Knew Brahms, tracks Nancy’s trajectory from a teenage library assistant to the Philadelphia Orchestra to the assistant to the legendary Leopold Stokowski. Nancy had, without a single audition or music degree, inserted herself into the bloodstream of classical music.

There was a fairy-tale prologue. After weeks spent haunting the lobby, she was noticed by music director Eugene Ormandy. “I see you here every week,” he said. “Do you have a ticket?” Of course she didn’t. Ormandy, in a gesture now almost unimaginable, escorted her to the box office. “This is a friend of mine,” he told the clerk. “Can you please give her a ticket?”

The clerk, recognizing the interloper who previously could not afford one, looked her over: You? Now a friend of Eugene Ormandy? The absurdity delighted Nancy. And soon enough, she found the unguarded doorway backstage. The ticket takers became a formality she felt no obligation to indulge. There are, she reflects, “few places today where a fifteen-year-old could wander like that.”

Inside, she entered the waning era of the “podium dictators”, conductors whose genius came bundled with tempestuous authority. “Stokowski, like Toscanini, was one of the terrifying conductors,” she says. “These weren’t nice guys.” Yet Nancy, preternaturally composed, disarmingly unawed, was undeterred. “I didn’t find them difficult,” she shrugs, imagining they were “charmed by a very young girl obsessed with the music.”

Obsession, yes, but also a form of inquiry. Nancy wanted answers. Why this tempo? Why that silence? Why, precisely, did music behave the way it did?

In February 1964, she staked her future on a question. Stokowski was rehearsing Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony; the session was closed. Nancy stationed herself outside on a brutal winter morning, waiting for his arrival. When he emerged, towering, white-maned and mythic, she dashed after him. “Maestro, may I come into your rehearsal?” she blurted.

He stopped, startled that anyone would dare. Then came the unimaginable concession: yes. On one condition. “You must come backstage after the rehearsal and tell me your impressions.”

She treated the assignment like a doctoral defense. When the time came, she marched into his dressing room and, eschewing flattery, launched into analysis: Why had he slowed the orchestra in a passage she had never heard played that way? Rather than dismiss her, Stokowski opened his score and explained. The following week, she appeared again, uninvited this time. He waved her in. And so, it continued: for the rest of his life, she would be welcomed at any rehearsal he led.

Nancy was a young woman in a world still profoundly suspicious of female presence. In 1964, the Philadelphia Orchestra counted only four women among its ranks. And yet, she was not alone.

Her memoir is meant as a form of hospitality, a “literary welcome mat.” She rejects the notion that classical music demands advance study. “You have as much right to that seat as a music critic does,” she insists. “You do not need to know anything. Just open your ears. Open your heart.”

Only now does she recognize the daring embedded in her young self. Others call it courage; she calls it necessity. “What did I have to lose?” she asks, the rhetorical simplicity belying a girl who had already fled one kind of danger for another kind of hope.

Nancy Shear told a friend: There is no doorway and no lock strong enough to keep me out of the concert hall. The woman who once slipped through an unattended stage door now holds it open, gently, defiantly, for everyone else.