Hear the Conversation | Get the Book

In 2018, Heather Ogden was a high-school student, freshly steeped in Orwell’s 1984, when she had a dream she can no longer remember. What remained was not the dream itself but its residue, the sense of a plot, of a story that wanted telling. At first, she imagined it as a film script. Cinema was her first love. But the path to Hollywood is narrow and forbidding, and Heather, pragmatic in the way dreamers must sometimes be, chose prose instead.

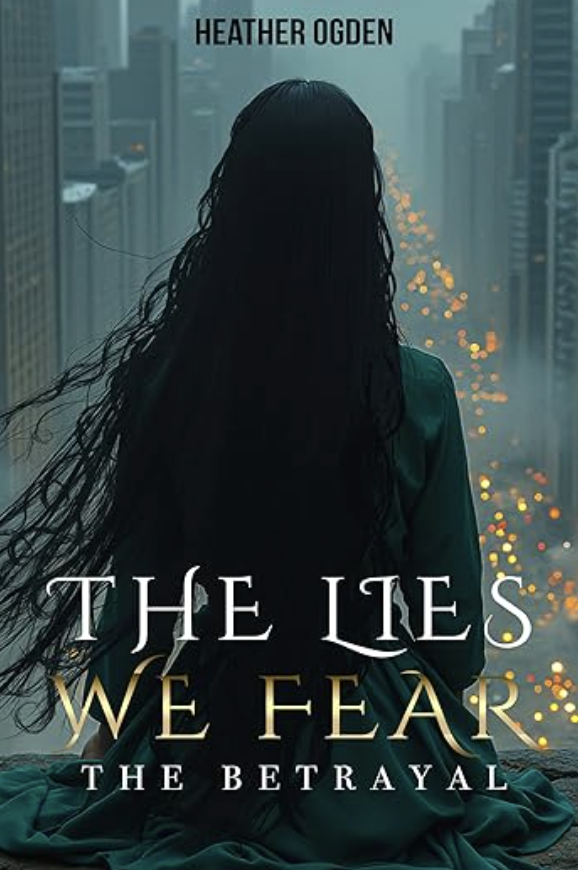

Her debut novel, The Betrayal, is the opening salvo in The Lies We Fear series, a dystopian fantasy in which loyalty is weaponized, truth is elusive. And love itself is a form of coercion. At its center stands Angelette Arabella, the daughter of a national hero, whose life unravels when a staged kidnapping exposes a lattice of lies. The novel’s cityscape, Libertus, is a place at once modern and fantastical, New York by way of Chicago, with the gleam of skyscrapers and the menace of shadows. Heather wanted her readers to feel the overwhelming thrum of a metropolis and, simultaneously, the uncanny shimmer of a world that might be real.

“I chose betrayal because everyone has felt it,” she explains. There is something disarmingly straightforward in her logic. Betrayal is both universal and a wound that can unite readers with characters. The act of being deceived, and of surviving it, is fertile ground for empathy.

Heather is quick to clarify that her novel’s fraught father-daughter dynamic is not autobiographical. Her own father, she insists, is supportive and kind. But she immersed herself in psychological research to imagine what power and control, when filtered through a parental bond, might do to a young woman’s sense of self. In this way, The Betrayal joins the lineage of dystopian narratives that render family life as a crucible of ideology: Orwell’s Party, Atwood’s Gilead, Collins’s Panem.

Heather’s prose bears the marks of her early training in screenwriting. Dialogue comes to her easily; she hears her characters speaking in her head and transcribes their voices onto the page. What she struggles with, she admits, are the connective tissues, description, transition, the slow work of building atmosphere. And yet the book’s cinematic pacing is precisely what her readers notice: cliffhangers at the end of chapters, a rhythm designed to propel rather than pause. She already envisions the trilogy as a film, one she hopes to script herself, bridging the gap between her first passion and her current one.

The book’s path to publication was as improbable as its premise. When she submitted four chapters to Morgan James Publishing, she had no expectations. Then came the call: yes. In a panic of exhilaration, she wrote thirty-six chapters in a week, a fury of invention that belies her description of herself as an introvert paralyzed by social anxiety. Public readings and conferences are ordeals. At one writer’s festival she wore earplugs to stave off the sensory overload. She admits that her greatest fear is not failure but success, being forced into visibility. Yet her greatest joy is also clear: the act of writing itself, the quiet exchange between mind and page.

Heather’s characters, she says, sometimes take over. During high-intensity scenes, she writes too quickly, pouring entire climaxes into a single chapter before realizing she must pull back. She is learning the art of pacing not just her plots but her own adrenaline. In this sense, writing is both craft and self-regulation.

The young novelist speaks openly about imposter syndrome. She remembers showing her mother a script in middle school, only to dismiss the maternal praise as biased. Even now, she wonders whether her family’s compliments are rooted in affection rather than objectivity. She has received five-star reviews, but the suspicion lingers. Perhaps it is this doubt, more than anything, that keeps her writing.

What Heather hopes readers take from The Betrayal is deceptively simple: that truth matters, even when the world is built on lies. She quotes Robert Evans, “there are three sides to every story, yours, mine, and the truth”, as if it were a lodestar. In Angelette Arabella’s world, deception is systemic, almost structural; yet to seek truth, however partial, is an act of bravery. It is, implicitly, the task of both the character and the reader.

Heather lives in Tennessee, where she haunts bookstores not just for the volumes but for the scent of new pages. She listens to gossip in cafés, filing away fragments of overheard drama for future use. Like many writers, she moves through the world half-present, half elsewhere, her imagination always foraging. The Betrayal may be her debut, but the series is already mapped: cliffhangers, shifts in perspective, revelations queued like dominoes.

It is a curious thing to meet a writer at the beginning of her arc. Heather Ogden is twenty-something, modest, a self-described introvert. And yet she has produced a dystopia both vast and intimate, a city of lies where betrayal is currency and truth the rarest weapon. She insists she is still learning, still surprised. But then, the best dystopias are written by those who doubt not just the world but themselves.