Hear the Conversation | Get the Book

Five months after the sea rose and devoured the coastline of Sri Lanka, Sharon Eubank stood before a derailed train. When the thirty-foot wall of water came, fifteen hundred lives were extinguished in an instant. The survivors, stunned and unwilling to abandon the site, clutched at Sharon with broken words: I lost my baby. Can you help me?

Sharon was a professional in the mechanics of aid, a veteran of the endless choreography of trucks, manifests, distribution plans. Yet at that moment she had nothing. No bread, no soap, no token to place in a small hand. “I didn’t have anything,” she remembers. “Just misery.”

Her translator, a local man named Shanta, responded differently. From their van he produced a soccer ball. He rolled it into the dust and coaxed the children into play. Then he turned to the adults with the unhurried familiarity of a neighbor. How was the bread coming along? Did anyone need washing powder? He would look for some when he went to town. It was not much. It was everything.

Watching him, Sharon felt the ground shift beneath her. All her training, her connections, her access to the machinery of international relief, paled before a man with a soccer ball and a willingness to listen. Shanta was powerful because he belonged. That day in Sri Lanka became her conversion: the realization that aid fails when it descends from above, but blooms from within.

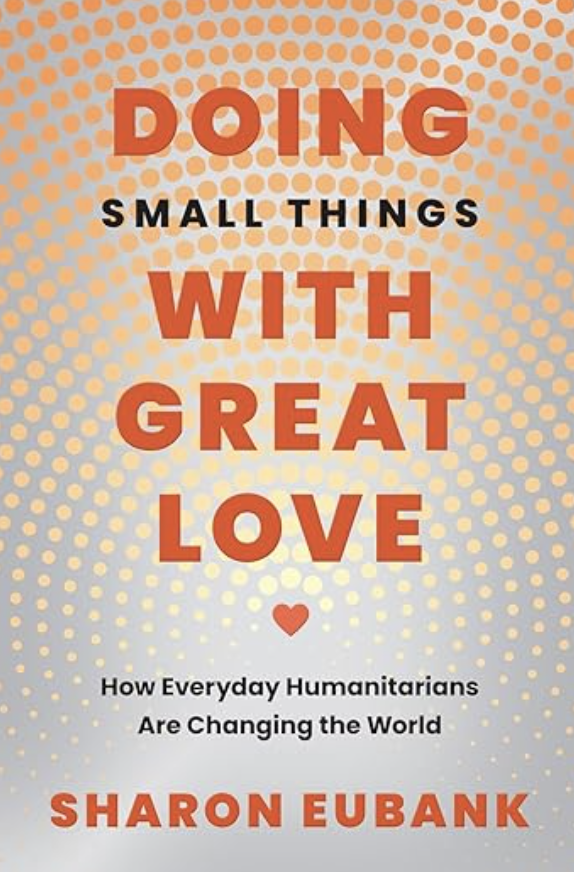

Her book, Doing Small Things with Great Love, is an extended meditation on that idea. The title, borrowed from Mother Teresa, gestures toward humility. Two trillion dollars have been spent in Africa over the last sixty years, Sharon points out, yet many of the continent’s most basic problems remain. The failure is not in money but in the faith placed in money. Purpose, is more decisive than scale or spreadsheets.

Purpose, in her telling, lives in what she calls “trusted networks”: the PTA, the church committee, the homeowners’ association. These groups are often ungainly, contentious, maddeningly small. They also work in ways that billion-dollar budgets do not. They know their people. They care about their block, their town, their neighbors. When aid flows through them, it takes root. When it bypasses them, it can evaporate.

She learned this lesson again, closer to home. During the Yugoslavian war, her mother sat at the kitchen table, knitting red slippers for refugees. Sharon initially underestimated the gesture. Years later, she read an article in which a woman remembered receiving handmade socks in a bombed-out building, a reminder that she was not forgotten. The slippers had not stopped a war, but they had restored dignity. Sharon felt the sting. “I had to apologize to my mom,” she says.

Her work has taken her to nearly two hundred countries, yet her conclusions are marked by paradox. The United States, she posits, is rich in material goods, yet poor in relationships. In Japan, she watched nine-year-olds refuse to answer a question until the group had conferred, an instinct toward consensus that felt both foreign and instructive. Again and again, she has seen that the great tasks of repair are never accomplished alone.