Hear the Conversation | Get the Book

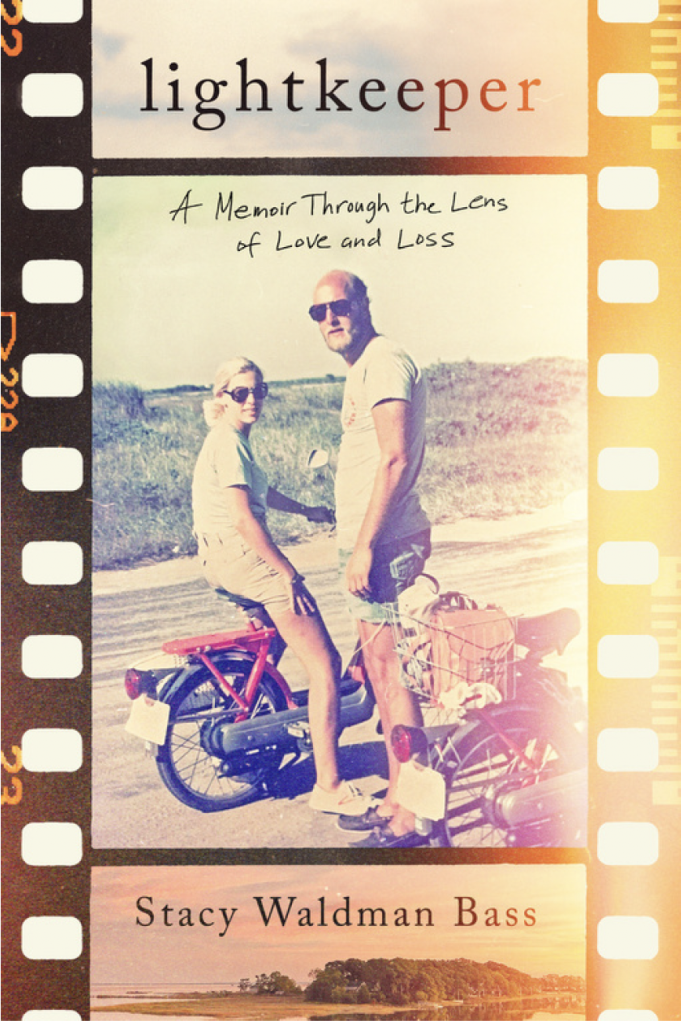

There are few objects more paradoxical than a photograph. It is, at once, a cage and a key: an image sealed in silver halide or digital pixels, yet able to conjure whole narratives from the invisible margins beyond its edges. Stacy Bass has staked her life’s work on this paradox. For her, photography is not simply the practice of catching light but of keeping it, keeping it when it wants to slip away, when time insists on dissolving it. Her new book, Lightkeeper: A Memoir Through the Lens of Love and Loss, is a testament to this devotion. To hold a photograph, she reminds us, is to hold a life.

The title was never negotiable. “I was really committed to it,” Stacy told me. It operates on several registers. At its most literal, it names her vocation: photography as the act of trapping light. But it also reveals her project’s deeper ambition, preserving the luminosity of those now gone. Stacy’s memoir is stitched together from two catastrophes: her father’s sudden death in a seaplane crash in 1995, and her mother’s year long decline from pancreatic cancer years later. Between these opposites, an abrupt severing and a slow surrender, she found both the shape of her grief and the structure of her book.

Cameras, Stacy recalls, were always in the household, her father’s enthusiasm filling the drawers with equipment. She remembers disposables at camp, cafeteria candids, early evidence of a visual instinct. When she turned to the internet for traces of him, she found only the bureaucratic language of the Federal Aviation Administration, a record of how he died, not of how he lived. That injustice became her call to arms. Every Father’s Day, every birthday, every anniversary, she posted his photograph online. In the middle of Facebook’s digital chatter, her posts were elegiac counterpoints, small rituals of resurrection.

With her mother, the ritual expanded. This time she had advance notice. She asked permission to begin a daily series of portraits. Her mother, practical as always, wanted to know the term. “A year,” Stacy suggested, a goal born of optimism. She called the project I Love You Mom. Soon the posts became a gathering place: friends asked about sweaters, about storefronts in the background, about the ordinary artifacts of life. For her mother, under the weight of chemotherapy, the ritual became fuel. The series was, in Stacy’s words, a love letter, one written and delivered in real time.

Grief, Stacy insists, is not an obstacle to overcome but a companion to accommodate. She had no desire to “get over it.” To do so, she felt, would mean loosening her hold on her parents’ memory. Instead, she sought to let beauty and sorrow coexist, to enlarge her capacity for both.

The act of writing provided its own form of expansion. Putting words to paper was a means of reordering grief. Reading them aloud became something else entirely. Recording the audiobook, Stacy allowed her voice to crack, to fracture, resisting the impulse to polish emotion into neutrality. After her father’s passing, she had searched in vain for recordings of his voice. With her mother, she was determined to preserve an audio memory. She recorded their conversations just to preserve the cadence. She doesn’t listen daily, she says, but she knows they are there, waiting for the moment when silence grows too loud.

Memory, Stacy argues, is messy; its authenticity lies in its untidiness. In the book’s most luminous passage, she recounts finding a honeymoon slide of her mother, taken by her father, a photograph she had never seen. The discovery startled her into an intimacy with a woman who was not yet a mother, not yet bound by the demands of family. The photograph transported her to a moment that belonged wholly to her parents, before her own life began. The image was a gift across time, a portal that let her imagine what could never be told.

Stacy’s artistry reminds us that photographs are not endpoints but invitations. They invite us to imagine the seconds before and after the shutter, the stories that seep from the edges of the frame. In Lightkeeper, grief is not only endured but curated, illuminated, and shared.

Through prose and picture alike, Stacy Bass demonstrates that light, once caught, can be kept, that loss, though it darkens, can also be radiant.